The fitness-related content on this site has all been moved over to Strengtheory.com, my new website.

If you want to keep reading on this page, that’s perfectly fine. If you want to read this article on Strengtheory, just replace “gregnuckols” in the address bar with “strengtheory,” and don’t forget to check Strengtheory.com regularly for new articles! If you’d like to share this article with your friends (please do!), then I’d appreciate it if you shared the Strengtheory.com URL. It’s a prettier site for your friends to use, and it helps with the new site’s ranking in search engines.

If you want to get stronger, training volume and intensity are the two most important variables, right? Well, a recent (May 2014) study published in the European Journal of Sports Science sheds some light on another crucial factor – bar speed.

Now, if you’re like me, you’ve always heard that you’re supposed to lift the bar (concentric) as fast as possible, and that doing so would recruit more fast twitch fibers since you’re producing more force, and more muscle fibers activated = more gains.

However, I’ve never heard anyone pinpoint how much of a difference maximum rep speed actually made – at least not with any credible sources backing them.

Well, this recent study – Maximal intended velocity training induces greater gains in bench press performance than deliberately slower half-velocity training – suggests that it makes a huge difference:

Approximately double the strength gains by lifting the bar with maximum speed each rep, as opposed to a slower cadence, even when equating training volume and intensity. VERY cool. Personally, I would have expected a difference, but not anything THAT dramatic.

Let’s dive in.

Background

As I previously touched on, the thinking behind lifting the bar as fast as you possibly can is this:

1. To produce more force, your body uses more muscle fibers (as opposed to each fiber just contracting harder to produce more force)

2. The first fibers your body uses are the smallest, slow-twitch fibers. To produce more and more force, it recruits progressively larger and stronger fibers, with your largest, strongest fast twitch fibers being the last ones integrated into the movement. (This is called Henneman’s Size Principle)

3. Recruiting these fibers isn’t based on the weight you’re using per se, but rather the amount of force you produce. Force = mass x acceleration, so all other things being equal, lifting a bar faster means you produced more force to lift it.

4. Therefore, lifting the bar faster recruits more muscle fibers.

5. The fast twitch muscle fibers – the last ones you recruit – are the ones most prone to hypertrophy, so lifting faster = more fast twitch fibers used = more strength and size gains.

Sounds great in theory, right? Except…

The bulk of the previous research looking at the effects of lifting velocity on strength gains showed that there was no significant difference between lifting as fast as possible and lifting at a slower cadence.

Oops. That theory sounded so appealing and straightforward a moment ago.

But wait a second – as the authors in this current study point out, much of the past research on the subject was methodologically flawed.

1. Many of the stuides didn’t equate load and volume. This was a problem with the studies that HAD shown intentionally lifting fast was better than intentionally lifting slower. If you’re intentionally lifting the bar slower, you’re not going to be able to handle as much weight or volume, so of COURSE the protocol lifting at maximum speed would yield better results – but you have no idea whether it was the bar speed itself that mattered, or whether it was simply the difference in intensity and volume.

2. In the bulk of the studies showing no difference in lifting fast vs. lifting slow, they were doing sets taken to failure, or close to failure. Going back to Henneman’s size principle, another application of it is that as the first fibers you recruit start fatiguing, you recruit larger and stronger fibers to take their place to keep producing force. Also, many of those studies weren’t volume-equated either. Additionally, regardless of what the cadence was SUPPOSED to be, when taking sets to failure, all your reps eventually end up being slow! So with these studies, the differences in ACTUAL bar speed weren’t substantial, and the real takeaway is that if you push yourself to failure, rep speed doesn’t matter as much.

But what if you don’t WANT to train to failure for all your sets, all the time (i.e. most of us)? Well, that’s where this study fills in some gaps.

Subjects:

24 men were recruited (4 dropped out), mostly in their early to mid 20s, and of normal height and weight (1.77 ± 0.08m, 70.9 ± 8.0kg). They were healthy and physically active, with 2-4 years “recreational” experience with the bench press. “Recreational” is a slippery term. Their 1rms averaged around 75kg to begin with – slightly more than 1x body weight. So it wasn’t the first time these guys had picked up a barbell, but they also weren’t elite athletes.

Protocol:

The subjects maxed at the beginning and end of the program to assess strength gains. Also, bar speed of all of their warmup sets was recorded (both groups were instructed to lift the bar as fast as they possibly could on all of their warmup sets) to see whether training fast or slow affected their force production capabilities.

They split the subjects into two groups. Half of them trained at max velocity (MaxV – controlled eccentric, and explosive concentric), and half of them trained at half velocity (HalfV – controlled eccentric, and 1/2 maximum bar speed for the concentric). They benched 3x per week for 6 weeks, then assessed results.

The way they made their weight selections for each day was *very* interesting. Prior research had found that average concentric bar velocity (how fast you can push the bar up) correlated very strongly with given 1rm percentages for bench press.

An average maximum bar speed of 0.79m/sec means you’re lifting about 60% of your 1rm, 0.70 m/sec is about 65%, 0.62m/sec is about 70%, 0.55m/sec is about 75%, and 0.47m/sec is about 80%.

| Average concentric velocity (m/sec) |

Percentage of 1rm |

| 0.79 |

60 |

| 0.7 |

65 |

| 0.62 |

70 |

| 0.55 |

75 |

| 0.47 |

80 |

To make sure they were using, say, 75% of a subject’s ACTUAL 1rm for the day, rather than 75% of their initial 1rm (which would become outdated as they got stronger over 6 weeks), the researcher would have the subject lift each warmup rep as fast as possible, until their average concentric bar speed was 0.55m/sec. That would be their working weight for the day.

(As an aside, a common knock against percentage-based programs is that you have a harder time accommodating good days and bad days. As your strength fluctuates, 80% of your all-time PR may not actually be 80% of your actual strength for the day. Using bar speed as a way to approximate percentage of 1rm may be a smart way to account for daily fluctuations in a percentage-based program)

So, on 75% day, the people in the MaxV group would warm up, find the heaviest weight they could lift at .55m/sec, and do the assigned reps for the day. The HalfV group would warm up, find the heaviest weight they could lift at .55m/sec, and do the assigned reps for the day, but with an average concentric velocity of ~0.27m/sec, with visual and auditory feedback from a screen in front of them letting them know if their cadence was too fast or too slow.

There were 48-72 hours between training sessions.

On week 1, they did 3 sets of 6-8 with 60% each day, eventually progressing to (decreasing volume, increasing intensity – kosher linear periodization) 3-4 sets of 3-4 reps on week 6.

The study was impressively well-controlled. Here’s a great little line: “Sessions took place under supervision of the investigators, at the same time of day (±1 h) for each participant and under constant environmental conditions (20°C, 60% humidity).”

Time of day matters because circadian fluctuations in hormones like testosterone and cortisol may affect the training outcomes. Additionally, heat and humidity can affect performance – if it’s too hot and humid you’re more apt to fatigue because of thermal stress or dehydration, and if it’s too cold you can have a harder time getting warm and performing well. Studies like that are *supposed* to control for environmental factors, but many don’t (or at least they don’t explicitly stay that they did).

Along with the training study, the researchers did another study with different subjects to assess metabolic effects of lifting with different bar speeds. In this study, subjects came in, had their blood drawn, performed one of 6 routines (3×8 @60% with MaxV or HalfV, 3×6 @70% with MaxV or HalfV, and 3×3 @80% with MaxV or HalfV), and had their blood drawn again to assess lactate and ammonia concentrations.

Additionally, fatigue was assessed based on changes in the heaviest load the subjects could move at an average velocity of 1.0 m/sec pre-workout vs. post-workout

Results:

Before the training, there were no significant differences between the MaxV and HalfV groups.

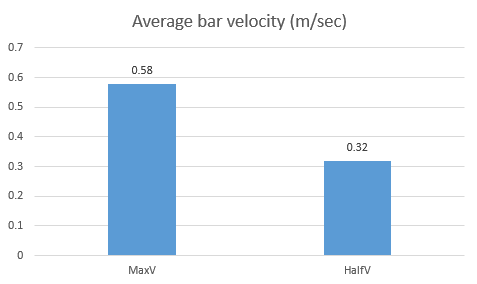

Average concentric speed WAS faster for MaxV, as you’d expect (0.58 ± 0.06 vs. 0.32 ± 0.03 m/sec)

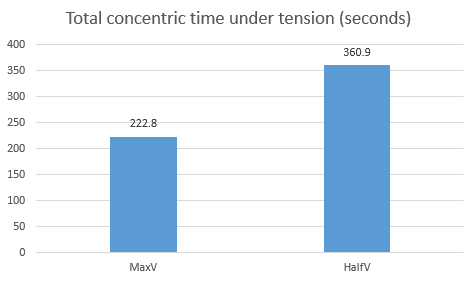

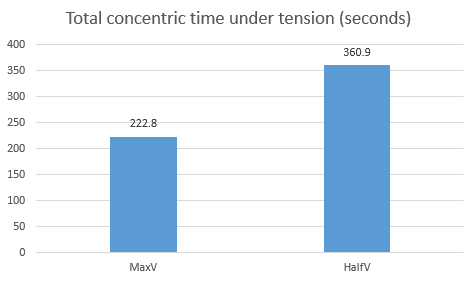

HalfV spent more concentric time under tension (360.9 ± 19.2 vs. 222.8 ± 21.4 sec)

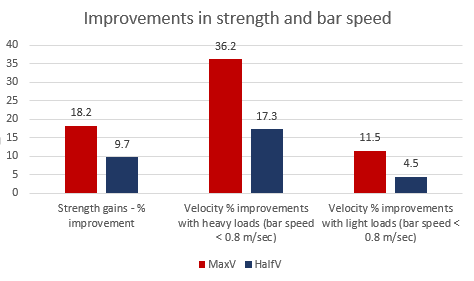

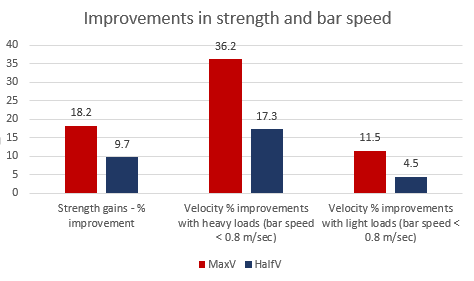

In every single category, MaxV saw basically twice the gains of HalfV

1rm bench press: +18.2% vs. +9.7%

Average velocity with weights they could move faster than 0.8 m/sec at both the beginning and end of the study: +11.5% vs. +4.5%

Average velocity with weights they could move slower than 0.8 m/sec at both the beginning and end of the study: +36.2% vs. 17.3%

Notice – right around 2x the gains across the board

In the metabolic study, there was actually a larger rise in lactate in the MaxV protocol vs. the HalfV protocol for both the 60% and 70% workouts, and fatigue (as assessed by the heaviest load they could move at a set speed) was greater in MaxV than HalfV on the 60% workout (7.6% vs. 1.4%), with a trend (that didn’t reach significance) toward more fatigue with the 70% workout as well (7.1% vs. 3.9%).

Now, take the lactate and fatigue data with a grain of salt – both protocols reached pretty moderate levels of lactate (we’re not talking about the metabolic difference of a heavy triple vs. a max set of 20 reps) that may not make a meaningful difference, and the standard deviations for fatigue were pretty large. They’re interesting trends to see, but any tentative conclusions drawn from them need to be even more tentative than usual.

There were no ammonia differences for any of the protocols.

Breaking is all down:

So, lifting the bar faster means more gains, and it makes you more explosive with lighter weights too? Sweet.

Not so fast.

Remember the issues with past research? This showed that when you equate for training volume and intensity and when you’re not training to failure, lifting faster may produce superior gains in maximal strength.

Additionally, the improvements in bar velocities with concrete loads doesn’t necessarily mean faster training makes you faster. If you’ll notice, the degree of improvement in bar velocity was pretty similar to the degree of improvement in 1rm strength.

Essentially, let’s say you bench 300. 50% of your 1rm is 150. If you get your bench up to 400, you’ll almost certainly be able to move 150 faster than you could when you benched 300. But will you move 200 faster than you used to move 150? Maybe, maybe not, but this study at least seems to indicate that it wouldn’t have to do much with whether you were training fast or slow – the larger gains seen in the MaxV group were with absolute loads, not loads relative to their new 1rms. The biggest takeaway is that being able to pick up heavier things makes it easier for you to move lighter things faster.

Another interesting thing about the improvements in velocity: For both groups, larger gains were seen in bar speed for heavier weights (ones they moved slower than 0.8 m/sec; 17.3-36.2% improvement) vs. gains in bar speed for lighter weights (ones they moved faster than 0.8 m/sec; 4.5-11.5% improvement). This has implications for pure power athletes. Getting stronger DOES help you produce more power, but it’s not highly specific. Lifting heavy things has a much higher carryover for lifting heavy things fast than it does for lifting light things fast.

So will you be able to throw a shot put further by increasing your bench, or be able to jump higher by increasing you squat?

Absolutely! To a point… After that time, training specificity becomes a bigger concern, and the carryover you get from producing force against something really heavy (training for an 800 pound squat or an 600 pound bench press) becomes increasingly less if your goal is to be able to produce a lot of force against something relatively light (your body or a 16 pound ball). This is an aspect of training specificity people don’t talk about quite as much. Training is specific to the muscles and movements you train, sure, but it’s also specific to the velocity you train with.

Going back to fatigue and lactate for a moment – more fatigue and lactate accumulation with the MaxV protocols may indirectly indicate a larger reliance on fast twitch fibers (as Henneman’s Size Principle would lead you to expect). Fast twitch fibers are more fatiguable than slow twitch fibers, and they rely more on glycolytic energy systems. However, the differences between the two protocols were really pretty minor in both these regards, so an indirect conclusion based on shaky foundations shouldn’t be something you put TOO much confidence in to account for the difference in training effects.

One thing I really loved about this study was that it actually recorded average velocities and concentric time under tension. TUT has been preached by some as a driving force in strength and hypertrophy gains. However, the HalfV protocol had substantially more TUT than the MaxV protocol, but it produced substantially worse results. Perhaps TUT should be amended from “time under tension” to “time under maximal tension” – how much time you spend actually moving the weight with as much force as possible.

Of course, that runs counter to the pretty little 4 number notations people like to use (3-1-3-0 would mean 3 second eccentric, 1 second pause at the bottom of the rep, 3 second concentric, and 0 second pause at the top before the next rep). This study seems to suggest that for maximum strength gains, you may dictate a certain cadence for the eccentric, and time at the top and bottom, but the concentric should be completed as fast as possible.

Now, before we throw the baby out with the bathwater, there is a time and place for controlled concentrics – learning. If someone has poor awareness or is trying to fix a technique flaw, slowing down the concentric while focusing on appropriate cues can help reinforce proper technique. If someone can’t perform a movement properly slowly (weightlifting aside), they probably aren’t going to be able to perform it properly at maximal velocity. You can also use controlled concentrics if you want to practice a movement for the day, but want to employ a means of naturally limiting how much weight you can use for the exercise. However, for most lifts, most of the time, it’s probably most beneficial to lift the move the load as fast as possible.

One last thing to point out from this study: you DON’T constantly have to train to failure or close to failure if you want to get strong. Sets of 3 at 80% (an ~8rm weight) or sets of 6 at 60% (a ~12-15rm weight) aren’t going to be incredibly difficult. But the MaxV group averaged gains of about 30 pounds on their bench in 6 weeks – not too shabby! The frequency in this study (benching 3x per week) was fairly high, and the weekly volume (36-60 reps between 60-80%) was fairly high too considering the strength and experience of the trainees. However, I’d wager than none of their sets pushed them within a rep or two of failure. Total training volume is more important than running yourself into the ground every set.

Wrap-up

When not training to failure, moving the bar as fast as possible probably produces better gains than intentionally slowing your rep speed.

When you’re constantly training to failure, it may not matter quite as much. However, you DON’T constantly have to train to failure to get stronger.

Moving heavy things as fast as possible improves your ability to move heavy things fast much more than it improves your ability to move light things fast.

You can use bar speed as an indicator of your strength day-to-day. You can use this knowledge to adapt a percentage-based program to fluctuations in strength day-to-day and (hopefully) improvements in strength over time without having to max in the gym regularly.