This is a pretty cool study. It’s the first paper comparing hypertrophy in high rep/low load and low rep/high load training NOT to failure. This is important because people often claim that muscle growth is the same between high and low load training only if the low load sets are taken to failure. However, as far as I’m aware, no one had actually investigated that idea. We know that if sets are taken to failure, hypertrophy is similarly. However, we don’t know that hypertrophy wouldn’t be similar if the sets stopped near (but not at) failure. One paper I recently reviewed in MASS came close to investigating this question, but the groups in this study not going to failure still went to what we’d call an RPE 10 (you didn’t fail a rep, but you couldn’t have done one more), which is how most people in the gym conceptualize going to failure anyways.

Briefly: A group of untrained young men performed knee extensions for 8 weeks. One group did 3 sets of 8 with 80% of their 1RM (something that should be pretty challenging, but not all the way to failure), while one group did 12 sets of 8 with 30% of their 1RM (a ton of sets, but each individual set should have been pretty easy).

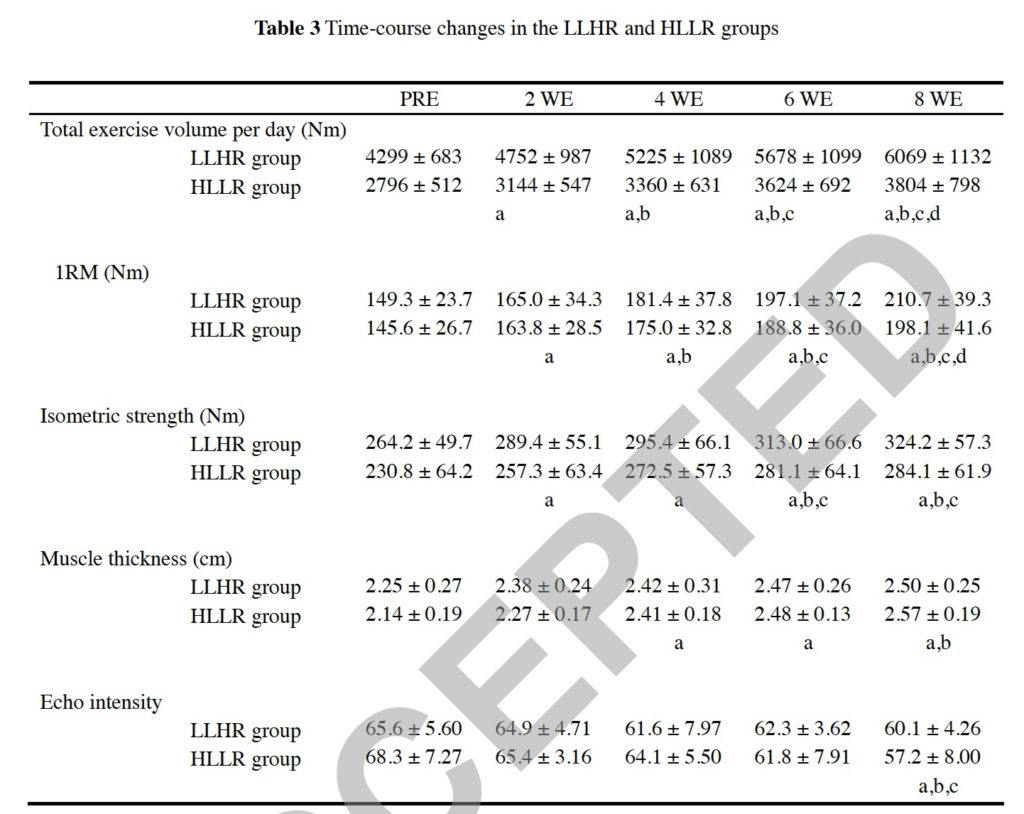

The researchers looked at isometric and dynamic strength increases and thickness of the rectus femoris (assessed via ultrasound). They took a few other measures, but those are the ones that are most important to us. 1RM tests occured once every two weeks.

They found no statistically significant differences in hypertrophy, but the raw percentage change seemed to favor the group using heavier loads (20.4% for the high load group vs. 11.3% for the low load group), so there may actually be a meaningful difference that couldn’t be detected due to low statistical power. Furthermore, strength gains were almost identical (40.9% for the low load group and 36.2% for the high load group for 1RM; 24% for the low load group and 25.5% for the high load group for isometric strength).

Let’s unpack this a bit.

I’m personally not a fan of how they went about keeping the high rep group from failure. There would have been a few “good” options (ordering is just my opinion):

Good: Match reps per set and relative volume. In this study, the 30% group did 4x as many sets, leading to a much higher relative volume. 80%×3×8=19.2. 30%×12×8=28.8. They could have, instead, compared 40% to 80%, and had the 40% group do 6 sets of 8. 40%×6×8=19.2.

Better: For each individual, have them perform a rep max test with their assigned load, then match the number of sets between groups, and assign reps for each individual based on a given percentage of the maximum number of reps possible with the training load. For example, if you put that percentage at 75% (doing 75% as many reps as they could do with a rep max test), and someone did 8 reps with 80%, you could have them do 8×0.75=6 reps per set. If someone did 28 reps with 30%, you could have them do 28×0.75=21 reps per set. Each set would get progressively closer to failure, but using something like 70-75% of max reps should keep people away from failure over 3 sets. Loads and reps could be reassessed after every max test.

Best: Use reps in reserve. People can accurately assign reps in reserve, even with low loads, within 1-2 reps to failure. They could have just matched the number of sets and kept people with an RIR of 1-2.

As it was, they didn’t equate any training parameter except for reps per set (which was probably the least important thing to equate), and didn’t even use a protocol that was ecologically valid (I doubt many people do 12 sets of knee extensions).

All of that being said, there was one thing that really interested me about this study. This study, much like the 50% vs. 80% Morton paper last year, included fairly frequent 1RM tests and, like the Morton paper, found similar strength gains in spite of big differences in loading. It would be cool to see a study specifically designed to investigate whether semi-frequent 1RM tests are enough to mitigate the strength advantage of high load over low load training.

Such a study could include 4 groups:

- A high load group only testing 1RM pre- and post-training (maybe week 0 and 12)

- A low load group only testing 1RM pre- and post-training

- A high load group testing 1RM semi-frequently (maybe week 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12), and…

- A low load group testing 1RM semi-frequently.

If it turned out that simply hitting a 1RM every 2-4 weeks was enough to ensure a solid rate of progress, that would be very useful to know. It would allow coaches and athletes a LOT more flexibility in designing training programs, especially in situations where strength is an important goal but not the main goal.

p.s. I plan on doing more of these short study write-ups since my time to write full articles has been severely curtailed with grad school. Any time I DO have to write is devoted to MASS at this point.

p.p.s. That probably won’t happen, but a boy can dream.