The fitness-related content on this site has all been moved over to Strengtheory.com, my new website.

If you want to keep reading on this page, that’s perfectly fine. If you want to read this article on Strengtheory, just replace “gregnuckols” in the address bar with “strengtheory,” and don’t forget to check Strengtheory.com regularly for new articles! If you’d like to share this article with your friends (please do!), then I’d appreciate it if you shared the Strengtheory.com URL. It’s a prettier site for your friends to use, and it helps with the new site’s ranking in search engines.

One of the biggest problems we have when we talk about training is that we tend to only talk about physical stressors.

We like complicated periodization models, manipulating training volume, intensity, and frequency. In short, we like having a sense of control. We like thinking, “If I plan out and control these training factors, I’ll get this outcome.” Sure, nutrition and sleep play a role too, but as long as those factors (often given the blanket term “recovery”) are accounted for, you’re in the clear.

However, those factors don’t paint the whole picture. Biology is messy. Your body is not a simple machine that you can feed inputs and expect predictable outputs.

Now, you can have a general idea of what’ll happen. But 1+1 doesn’t always equal 2. Maybe it’ll be 2 most of the time, but sometimes it’ll be 5, and sometimes it’ll be -3. The reason is that your body isn’t in a static state, only being challenged by the workouts you put it through. There are billions of reactions taking place in your body every moment affecting what’ll happen at the systemic level, while dozens of inputs are simultaneously entering the system via your thoughts and your senses (which then affect and modify other thoughts and sensations). 1+1 won’t always equal 2, because your body isn’t dealing with 1+1. It’s dealing with 1+1 plus a million other inputs and moderating factors. The result may be between 1.5 and 2.5 most of the time, but there’s plenty of built-in ambiguity that’s difficult to predict, harder to account for, and impossible to quantify.

Biology is nonlinear. You cannot control it. You can, at best, influence it.

Via trial and error, you can get a pretty good idea of how your body will respond to a certain set of training parameters. However, that response is still context-specific, and is largely mediated by how well your body can respond to stress. When you’re in a comfortable schedule with a 9-to-5, a predictable social life, no large sleep or diet perturbations, etc., you can develop a good idea of how your body will respond to training stress. The more constant the other inputs, the more predictable the result of imposing a particular stressor (training, in this case) will be.

However, increase the overall stress your body is coping with, and your ability to then cope with a given level of training stress is decreased. Although simplistic, Selye’s “General Adaptation Syndrome,” (pictured at the top of the article) is still very useful, even 80 years after its introduction.

Even if your training inputs haven’t changed, the rest of the inputs feeding into the system have changed, so the system with respond differently and perhaps unpredictably.

General Adaptation Syndrome essentially says that your body feeds all of its stress into a generalized pool of “adaptive reserves” that your body can use to elicit the specific adaptations necessary to respond to the stressor and strengthen the body against it in case the same stressor presents itself in the future. In the case of lifting, the strain on the structural and metabolic capabilities of the muscle are the stress, and your body responds by building larger muscles with more ability to resist strain and more of the enzymes necessary to handle exercise metabolically. However, if other stressors (work stress, poor sleep, heavy drinking, marital issues, moving to a new city, etc.) are present, they’re dipping into those adaptive reserves, so your body can’t respond as robustly to exercise.

This is something we all “know,” but which hasn’t gotten much attention in research. In fact, though specific stressors’ (sleep deprivation, food deprivation, high altitude, etc.) influence on exercise and subsequent adaptations have been studied for decades, there was actually only one measly study previously conducted on how general stress affects recovery from strength training, and it lasted less than 24 hours (i.e. not long enough to assess recovery on any meaningful scale).

However, now we have a brand new one which is really really good. It’s not a 12 week training study, but it’s – I think – useful.

Chronic Psychological Stress Impairs Recovery of Muscular Function and Somatic Sensations Over a 96-Hour Period by Stults-Kolehmainen et. Al. (2014)

The researchers sent out a questionnaire to 1200 people to place them on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Based on their PSS scores, the researchers purposefully sought out people who scored high or low on the scale to make sure there was a significant difference in stress level between the participants.

Participants

All the participants were enrolled in college weight training classes.

Once the subjects were selected, they were given two stress-related questionnaires. One was to place them on the PSS scale again (to see if their scores had changed since they last filled out the questionnaire), and one was the Undergraduate Stress Questionnaire (USQ).

PSS evaluates how stressed you *feel.* USQ evaluates how many stressful events are taking place in your life. This is a useful distinction to make, because some people tend to be able to just let the stress roll off their backs, so to speak. Others respond more negatively to life stressors. The high-stress group in this study both had stressful events in their lives, and felt mentally stressed about those things.

Procedure

The study procedure was pretty freaking brutal. The subjects worked up past a 10rm (i.e. they did sets of 10 until they could no longer complete 10 reps). Then they dropped back to their established 10rm for another set of 10. Then they took 10% off the leg press for another set of 10. If they got all 10 reps with that weight, they stayed with that weight and did 4 more sets to failure. If they didn’t get 10 reps, they took 10% more off and did 4 more sets to failure.

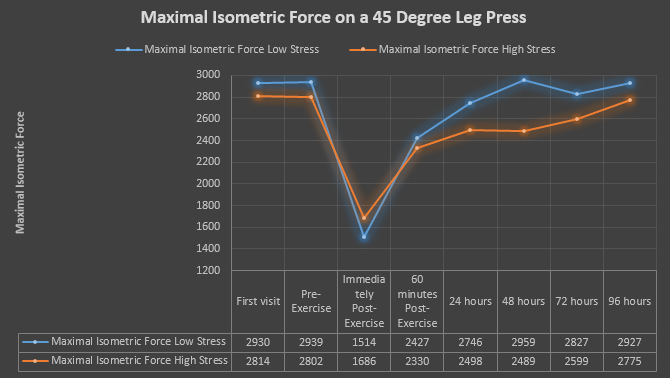

Before the training session, the researchers measured Maximal Isometric Force (using the same leg press – MIF), vertical jump height, and cycling power. They reassessed MIF directly after the workout and 60 minutes post-workout, and they reassessed all 3 performance-related variables at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours post-workout.

They also assessed soreness, perceived physical energy, and perceived physical fatigue before the workout, directly after, 60 minutes after, and at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours post-workout by having a number line with a statement like “I have no feelings of soreness” on one end and “strongest feelings of soreness ever felt” on the other end, and telling the subjects to place a mark on the line that corresponded with how sore they felt.

Results

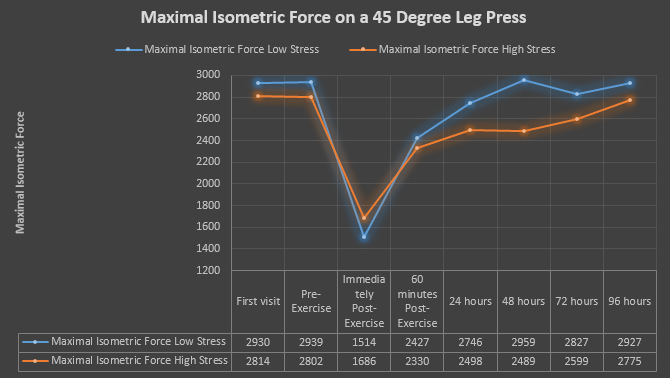

First of all, it should be noted that there were no significant differences in any of the parameters (MIF, 1rm strength, jump height, cycling power, etc.) between groups at the start of the study. Additionally, total workload and cardiovascular response to exercise (max and average heart rate) were similar between the high stress and low stress groups, indicating that the results can’t simply be explained by saying one group worked harder than the other.

Rate of recovery from exercise was strongly correlated with the stress inventories.

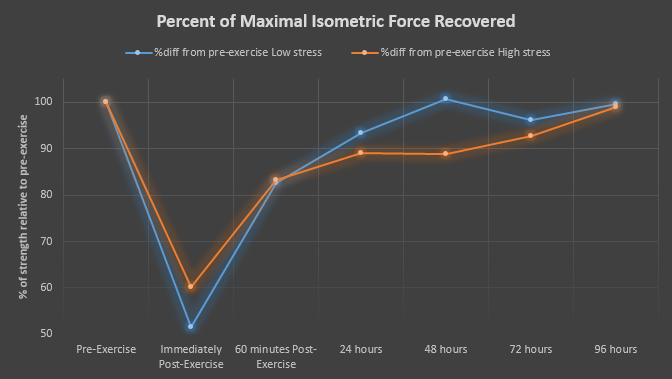

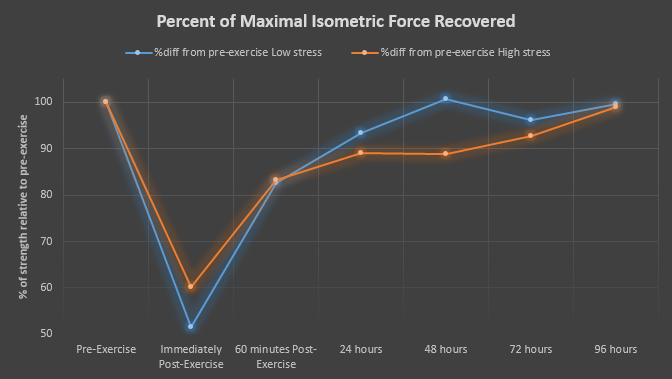

For Maximal Isometric Force, everyone was gassed after the workout, with strength dropping off almost 50% directly post-workout, recovering substantially at 60 minutes post-exercise, and continuing to improve from there.

However, the low-stress group had already fully recovered by 48 hours post-exercise, whereas it took a full 96 hours for the high stress group to recover pre-exercise MIF.

It should be noted – the researchers found this pattern by simply comparing the high stress and low stress groups. Then, to make sure there weren’t confounding factors, they made adjustments for fitness, training experience, and workload and found the same pattern still held true.

Cycling power and vertical jump height were less affected by the exercise bout, and recovered much faster in both groups – near pre-exercise levels by 24 hours post-exercise. The researchers theorized that this could be explained by specificity. MIF was assessed on the same leg press used as the workout, so that was the movement pattern showing the most fatigue.

Perceptions of energy, fatigue, and soreness were also affected by stress. The higher stress group had less energy, more fatigue, and more soreness for longer than the low stress group.

Takeaways

The results of your training can’t be reduced to how many sets, reps, and exercises you did. Other factors affect how your body will respond to exercise.

Furthermore, you can’t take your exercise performance in the gym today as an indicator of how hard you SHOULD be training, given other stressors. Both groups lifted a similar amount of weight, did a similar amount of volume, and had similar cycling power and vertical jump height.

That’s one factor that makes overtraining/overreaching tricky to manage. We like looking for objective signs – getting fewer reps, being able to lift less weight, etc. However, if this study is any indication, other stressors start interfering with exercise recovery prior to performance taking a major hit.

(Incoming aside)

One of the things that was difficult to adjust to when transitioning from training 90% of my clients in-person to training 90% of them online was that subjective feedback was harder to come by. When an athlete walks into the gym, you can tell from their body language, how they move, etc. whether they’re feeling good or starting to get run down – and you can make adjustments accordingly. You don’t get that if the only feedback you’re getting from your online training clients in objective.

Online, communication is so much more important. The sets, reps, and weights someone can lift only tell so much. You also need to know how they feel, how they’re sleeping, how their appetite is, etc. There were times that someone hit a huge PR one week, then took a nosedive the next week. I saw “this person has acclimated to the workload and is getting awesome results” when, in reality, they had adapted to the stressor as much as they were capable, and their performance peaked right before they started backsliding a bit. Lesson learned.

As hard as it is for people to accept (and trust me, I get a lot of push-back on this), I’ll usually deload someone directly after an unusually good week of training – steady, consistent PRs are one thing, but when an intermediate or advanced lifter hits a 40 pound PR out of nowhere, or gets 7 reps with a weight that was a max triple a month ago, I’ve found they’re usually teetering on the edge of overtraining – right when their results are telling them to push harder to see more big PRs. I don’t have any data to back me up, but it’s a pattern I’ve noticed enough times that I find it has good predictive value. 9 times out of 10, someone will hit a huge PR, I’ll pull back on the reigns for the next week of training, they’ll send me a few emails bellyaching, I’ll put my foot down, and on Tuesday or Wednesday I’ll get an email saying, “on second thought, the deload was a good call. Everything is feeling really freaking heavy this week.”

Physical fatigue often follows psychological fatigue, but the latter is harder to recognize without subjective feedback, meaning the former can creep up on you – or you can inadvertently rush headlong into it by putting your foot on the gas when the purely objective indications mislead you.

(Returning to our regularly scheduled program)

As was previously mentioned, the stressed-out people in this study both had stressful events taking place in their lives, AND they felt stressed about them. You can’t make any statements from this study about someone who has a lot of life stressors but who manages to stay feeling relaxed, or about someone who has fewer stressors but who still lets every little thing stress them out. My hunch is that the perception of stress matters more than the volume of stressors themselves, but this study doesn’t address that distinction. I’d love to see a follow-up study looking as people with high PSS scores, and low USQ scores (feel stressed without many stressors) and people with low PSS scores and high USQ scores (stressful life events, but minimal feelings of stress).

Interestingly, much of the research cited in this article had to do with wound healing. While the connection between muscle repair and wound healing isn’t 1 to 1, there are some notable similarities. Namely, both are mediated by the inflammation pathway to a large extent, and both are inhibited by glucocorticoid dysregulation. Psychological stress screws with cytokine signaling (including IL-6, IL-1b, and TNF-a) and results in a chronic elevation of cortisol.

In non-nerd speak, when your body’s stress response is switched “on” too much, for too long, the pathways that mediate the inflammatory response and tissue repair don’t work quite as well as they should. As a result, wounds heal slower and/or you take longer to recover from training.

Remember, you can’t just draw out a plan on paper, look at the volume, intensity, and frequency, and know how your body will respond to it 100%. What may be low volume and easy to recover from in a situation with minimal life stress may be high volume and crushingly difficult when other stressors in your life rear their heads. Ongoing adjustments need to be made, and some wiggle-room needs to be built in so you can alter your training stress based on what life throws at you.

This isn’t to say there’s no value in having a plan. It just means that plan needs to be interpreted more like a compass than like a road map.

Of course, ambiguity stresses some people out more than others. I love things that have a lot of gray area, while other people hate them, and want everything spelled out. In that case, a training plan with too much wiggle room can, paradoxically, cause more of the psychological stress that it was intended to moderate and account for. I think that’s one reason RPE-based training works so well for some people (people who can handle more gray area) but not-so-well for others (people who agonize about whether something was REALLY an 8RPE or not).

You are a psychosomatic being.

Psycho = mind

Soma = body

You can’t divorce the two. Mental stress can manifest itself as physical stress, and physical stress can manifest itself as mental stress.

Don’t be fooled into thinking the only thing that matters when it comes to training are the sets and reps you do in the gym.

Don’t be fooled into thinking the time between training sessions, the food you eat, and the sleep you get are the only things that matter when you talk about recovery. Those things matter, but so do the other events in your life, and your perceptions about those events.

Personal Anecdote

Managing stress is key for success in the gym. Here’s my own experience:

I started college as a triple major and double minor (History, Psychology, and Leadership, with minors in Economics and Mathematics). I started lifting again after a few years out of the gym the spring semester of my freshman years.

I got back to my old plateaus pretty quickly, but then progress slowed substantially for about 9 months as I took 19-20 credit hours per semester. At the end of my sophomore year, I decided to go with my heart and switch to Exercise Science. I dropped all my other majors and minors.

That summer, I interned at a gym. I only worked 3 hours per day, had very minimal life stress, slept as much as I wanted, worked out 3-4 hours per day, and generally enjoyed life. I added 100 pounds to my squat and ~175 pounds to my total in 3 months, destroying my old plateaus.

My first semester in the Exercise Science program, I took another 20 hours to get all my pre-reqs out of the way to make sure I’d be able to take all the upper level classes in the program (designed for 4-5 semesters) in my final 3 semesters. Progress = zero.

The next semester, I only took 12 hours, and all of my classes were incredibly easy. Stress was minimal, and I added another 100 pounds to my squats (in wraps this time, so realistically more like 50), 20 to my bench, and 80 to my deadlift.

The work situation in the first half of that next summer was a lot more stressful that I was expecting, and I got married in July, so not much training took place after that (nice long honeymoon, and then only a week before going back to school). I got weaker that summer.

This past year (last August to this August) has also been fairly stressful. My wife and I were angst-y because we didn’t really have a plan for what we wanted to do with our lives. There was some stress about jobs, finances, and grad school that would take way too long to explain in a blog post about training, but suffice it to say that training wasn’t my #1 focus. As a result – very slow progress. Still hovering around where I was strength-wise 15 months ago when I last competed.

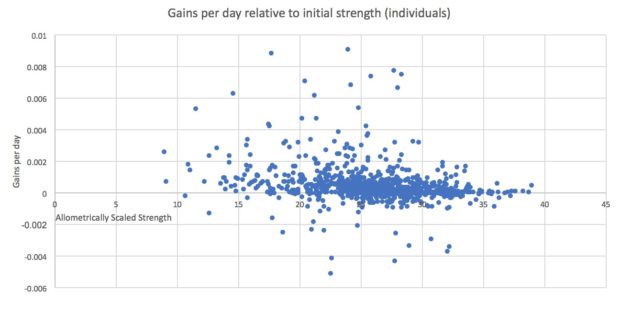

I like to look back and see what I was doing training-wise at peaks and valleys in my progress, but the factor that most strongly predicts how much strength I’ll gain at any given point in time – more than training (I totaled 1714 at 220 with a program utilizing daily maxes, and 1885 at 242 for a more kosher upper/lower-ish split) and more than diet (I was drinking the keto Kool-aid for most of my training time leading up to 1714, and had a more standard carb-based diet for 1885) is simply how stressful the rest of my life is outside the gym.

Anyway, just wanted to leave you with that anecdote.

Manage your stress and adapt your training plan to what life throws at you. You can’t separate your time in the gym from the rest of your life.